|

Using the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv as a base of operations, I have been conducting fieldwork in surrounding areas of the West with historical collections recorded for Camelina. My work has predominately focused on the Lviv oblast and the Rivne and Ternopil oblasts to the North and East of Lviv. Luckily, we were able to recover wild Camelina from several localities, many of which were distant from agricultural fields allowing us to sample potential variation in deferentially adapted populations. While in the field we decided to stop at the historical site of the Battle of Berestechko, a massive battle between Polish forces and Ukrainian Cossacks. Tens of thousands of Ukrainians died in these fields, and a monument, museum and church have been erected on the site. Another stop was that of Kremenets Castle, a 13th century castle situated on a steep hill overlooking the city of Kremenets. These steep and dry slopes are ideal for Camelina, and it was no surprise to find Camelina in thick patches growing all around the perimeter walls of the castle.

0 Comments

Lviv is a city in Western Ukraine which prides itself on the maintenance of traditional architecture and cultures. Here there are buildings which look much more "European" than in other areas of Ukraine, and for good reason. Lviv was not too long ago a city in Poland, but became incorporated into Ukraine after one of many of the city's change-of-hands. As such, a visitor in Lviv may confuse the city for being in Poland, not Ukraine. The city boasts a vibrant tourism industry with a wealth restaurants to enjoy and sights to see. Above, the Dominican Church in Lviv is just one of many magnificent churches in Lviv. The Dominican Church was originally constructed as a Roman Catholic church, and thus has a completely different style than Eastern Orthodox churches common throughout Ukraine. The Lviv Theatre of Opera and Ballet is the center piece of "Freedom Avenue", a lively walking street in the heart of Lviv. This building was constructed on top of the Poltva River which became enclosed underground, running directly under the theater. A common myth still circulates that the architect committed suicide after learning that the building was slowly sinking into the river below. You may still walk underneath the theater and see the now small stream running.

I started off my field work with three straight, and very long, days in the field. My goal was to collect as many wild Camelina populations as I could from as many distinct localities. My collaborators helped me to look over historical Camelina collection sites and we went back to many of these sites to see if Camelina could still be found. Unfortunately, after checking countless dozens of sites and seemingly-promising habitats, we only managed to find Camelina growing at a single location. We had scoured abandoned fields, ruderal areas, and the margins of crop fields, all with very little success.

I started off my work in Ukraine by looking through all of the Camelina specimens in the herbarium of the M.G. Kholony Institute for Botany. I was surpirsed to find very rare and old collections, the most interesting was without a doubt that of Ivan Schmalhausen, a Ukrainian born scientist who, among other endeavors, used Camelina as an evolutionary model system. As such, it was quite the honor to see his own collections of Camelina and other related species in Brassicaceae. Even better, the herbarium had several specimens from Nikolai Zinger, another early evolutionary biologist in the USSR using Camelina as a model system. Read more about these two soviet biologists in a previous post here. Next I visited the MM Hryshko National Botanical Garden in Kiev, where many thousands of lines of various food and ornamental crops are maintained and improved in breeding programs. Among these are several lines of Camelina! I had arrived just a little too late to see the Camelina growing, but the remains of harvested plants weren't difficult to find.  Here they experiment with different winter and spring varieties of Camelina and perform hybridization and growth experiments.

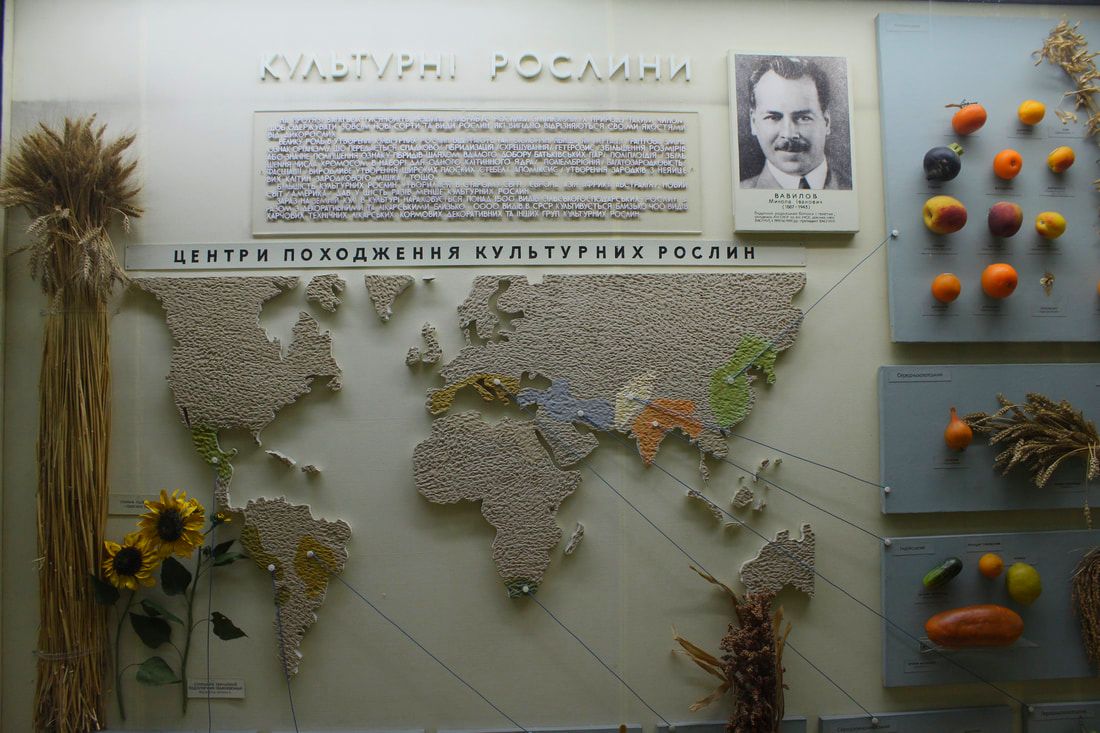

I'm now in Ukraine as part of the National Geographic Young Explorers grant supporting my work on Camelina. I'm still settling in - and recovering from my jet lag, but I've had a chance to see some of the city and meet my collaborator and organizer, Sergei Mosyakin. I feel like I've already learned so much about this beautiful country and its rich history; it's hard to believe I've only just begun this journey. The reconstruction of Ukraine's 11th century Golden Gates. Inside the National Museum of Natural Sciences of Ukraine, I found this great exhibit of the work of Nikolai Vavilov, my hero. His work took him all over the world to collect and preserve wild progenitors of many of the world's crop plants. Despite meeting a tragic and early death, his work was impressive and his drive to understand plant diversity and improve crop production is truly inspirational. The National Museum of the History of Ukraine. This large four-story museum extensively chronicles events and civilizations in the present day region of Ukraine, and boasts many interesting artifacts. My favorite exhibit was the history of currency in Ukraine, which sported ample examples of currencies used in the region throughout its history. In the coming days I will meet with local scientists and botanists in Kiev, while also organizing several small field collection trips that I will embark on in the coming weeks. Stay tuned!

I'm thrilled to announce that I'm the recipient of the National Geographic Young Explorers Grant! I have proposed a field collection trip for wild Camelina species in Ukraine. My goal is to discover wild populations of Camelina that may be predecessors to the domesticated Camelina sativa oilseed/biofuel crop. These predecessors may hold the key to understanding the evolution of this emerging aviation biofuel, but also give insight into the broader context in which plants evolve and become domesticated. I will be leaving soon for Kiev, Ukraine - be sure to follow my travel blog on my site to keep up with the adventure.

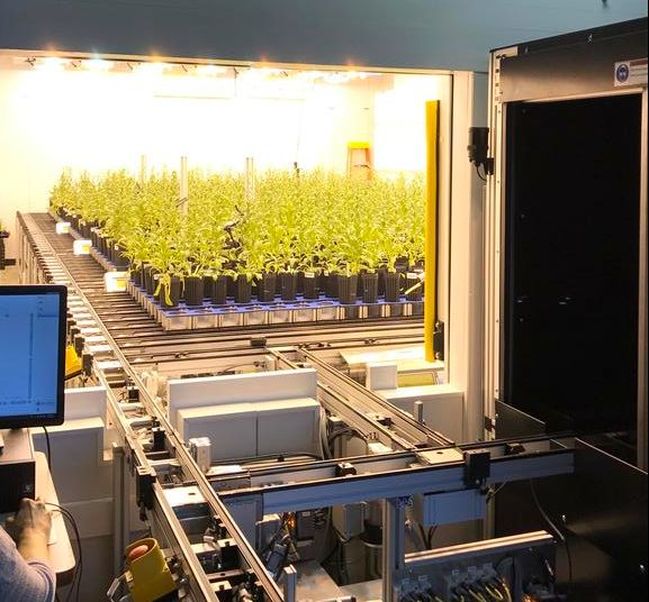

Variegation in plants is a phenomena in which leaf tissue partly or nearly entirely lacks green pigmentation. Variegation can occur in different colors and shades, mostly whitish or yellowish, and often lends ornamental value to the plants in which it occurs. As such, many common houseplants are variegated. Because variegation affects the pigmentation of leaves, and localization of chloroplasts (which provide plants all of their energy), it reduces the fitness of plants in the wild. While chance mutations do arise in wild plants leading to variegation, these traits are rapidly lost in wild populations. A few weeks ago I was working with some Camelina at the Danforth Center on a project using the Bellweather Phenotyper, and amongst the over 1,000 plants growing in the phenotyping growth house, we noticed one that looked visibly sickly from a distance. As the plants were cycled through the phenotyper, and the sickly individual got closer, I realized it was actually just variegated! It's the first variegated Camelina plant I've ever seen, and it looks awesome. There are many known mutations that can cause variegation in the close relative and model system, Arabidposis thaliana, so I won't speculate what could be the cause, and it's yet to be seen if this is a heritable trait.

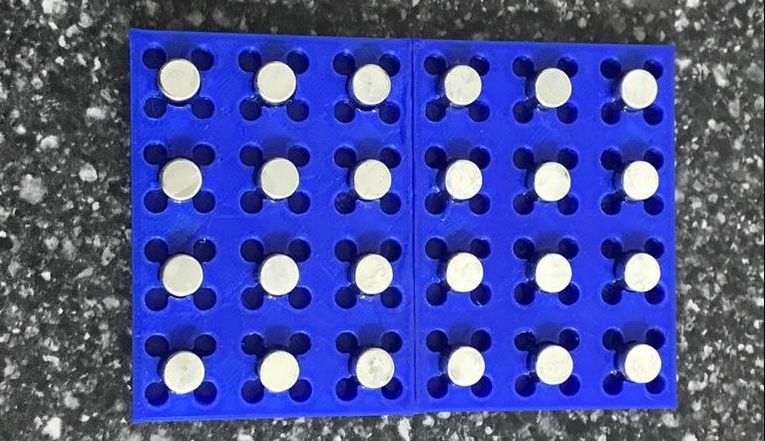

Upon the purchase of my 3D printer last year I have spent countless hours printing various board game pieces, and miniatures, but I hadn't actually got around to printing many useful items for my research. But now, the lab is now working on generating next generation sequencing libraries, and we have been borrowing much of the equipment from other labs. One piece of equipment, a plastic plate with strong neodynium magnets, is an essential component for bead purification clean-up steps. This seemingly inexpensive item sells for around $400 from the manufacturer, although it's really just some plastic and magnets. I did some snooping on Thingiverse.com and found this file for a 48-well magnetic bead separator plate - thanks to Ted Cybulski for uploading this design. I printed a single 48-well plate and purchased magnets (5/16" x 5/16") made of strong (N48) neodymium. I then affixed the magnets to my refrigerator one by one in the correct pattern, attaching the plate to make sure they are all in the perfect orientation. Next I applied a small amount of 2-part epoxy into each of the magnet slots and placed the plastic plate over the magnets on my refrigerator. I left it this way overnight to allow the epoxy enough time to cure, before removing it. Note that simply placing the magnets in the plastic plate will not work because their magnetic force is so great that they will fly right out. Also, these magnets must be treated with extreme care, as they may interfere with electronic devices (even at a seemly safe distance), and they tend to violently seek out metal to attach to. Finally, with magnetic plate in hand, a test trial was done and it was quite effective.  Finally, I reprinted two of the 48-well plates, assembled them individually as mentioned above, and then applied the 2-part epoxy generously between the surfaces of the two plates. I sanded each surface with a very fine-grain sand paper in order to ensure an even contact.

In all, this 96-well plate cost about $8 in magnets and plastic filament and took a few hours of printing time and assembly. Over the last hundred years, we have lost a huge amount of crop diversity in the form of cultivars and varieties of many crops. This 1983 study showed that nearly 93 percent of varieties in 66 crops studied had gone extinct since 1903. This bottleneck could have huge consequences on the ability for agriculture to adapt to a changing climate, but it is also a shame to have lost his diversity which undoubtedly harbored a range of flavors, shapes and colors of fruits and vegetables.

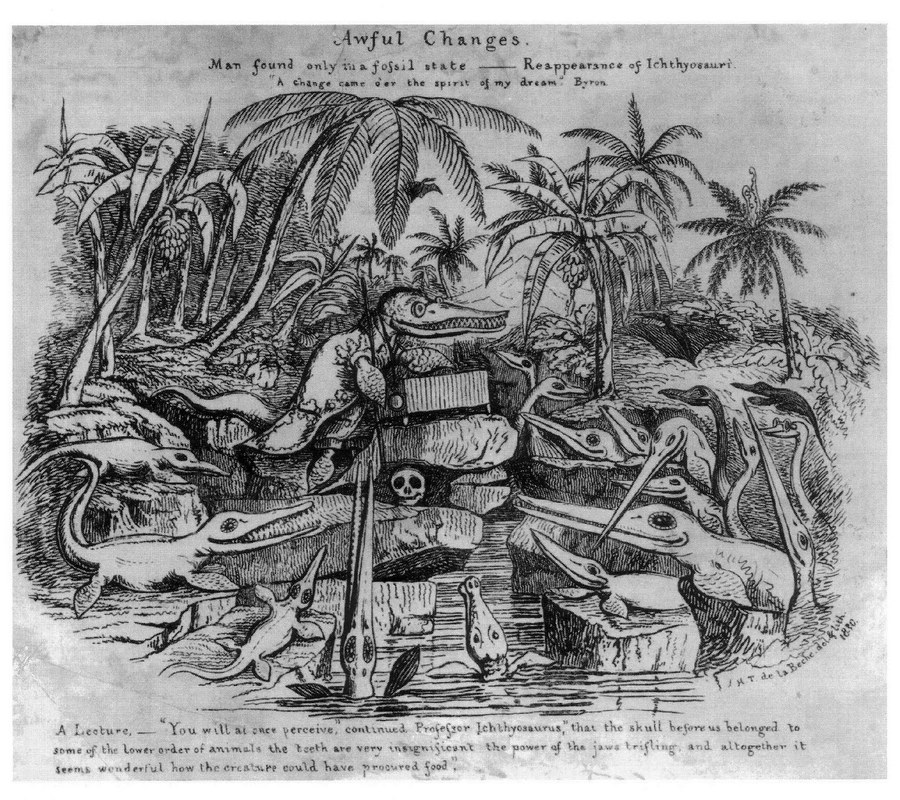

Saving and understanding as many varieties of crops as possible will serve to enhance our ability to improve them in the future. While conventional agriculture does rely heavily on monoculture, the benefit of saving the genetic diversity found in crop varieties can be leveraged in the future to introduce key traits such as drought tolerance, improved nutrition, and disease/pest resistance. One non-profit, Native Seeds/SEARCH, works to preserve delicate cultivars of a variety of crops grown by Native American tribes in the American South-West. Their engagement with the community, local farmers, and the research community represents the gold standard of community seed-banking. This is a great way to prevent the loss of delicate crop germplasm while engaging in community building, education, and scientific advancement. Henry De la Beche's "Awful Changes"

Professor Ichthyosaurus lectures: "You will at once perceive... that the skull before us belonged to some of the lower order of animals, the teeth are very insignificant, the power of the jaws trifling, and altogether it seems wonderful how the creature could have procured food." |

AuthorJordan Brock Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed